THE DAY BOKO HARAM ATTACKED

Postcards from Maiduguri, Nigeria.

WE WATCHED AS THEY EXECUTED PEOPLE

I was taken captive along with many other girls, and we were forced to witness horrible scenes, including the flogging of aged people and the slaughtering of those who disobeyed the insurgents. We were held in a big house in Bama, and many of the girls were dragged out and taken away for marriage to some commanders and fighters in various villages. I was forced into marriage with a Boko Haram commander, and I spent three years in captivity.

WOMEN WERE NOT ALLOWED TO GO OUT

The town remained under the control of Boko Haram for over six months, and I continued to live with my father under their rule. A woman wasn’t allowed to go out for whatever reason except to attend their so-called “lecture sessions”. I was flogged several times because I was out looking for what my father and I would eat.

WE SURVIVED ON LEAVES AND GRASSES

A few months after the school shut down, Boko Haram also attacked my village. They forcefully took me, together with other young girls and my grandmother, to their base in a village called Fada. The journey took some days. Many captives died along the way due to severe hunger, stress and tiredness. During the raid, many were also killed due to disobedience.

PEOPLE CALLED ME ‘BOKO HARAM DAUGHTER’

Fear and circumstances dragged me into a world I never truly belonged to. I was brought up in a family of Boko Haram. When I finally escaped and surrendered, I thought freedom would mean a new beginning. But I soon learned that freedom also carried its own struggles.

I WAS RAPED. I THOUGHT MY LIFE HAD ENDED.

Before the insurgency, I went to school every day and wanted to become a nurse so I could help women and children in my community. But all of that changed when Boko Haram entered our town in Bama. I was with my family at home when we heard gunshots and people screaming. In the confusion, I was captured along with other girls. That was the beginning of my darkest journey.

LIFE AFTER RESCUE FROM SAMBISA IS HARDER

The military launched an operation in Sambisa, and many of us were rescued. We were brought back to our original communities. At first, I hoped this would be a new beginning, a chance to rebuild my life. But since returning, I have found life incredibly difficult. I have no job, no steady source of income, and I spend most of my days being idle.

I ATE GOOD FOOD IN SAMBISA FOREST

At Sambisa, I was engaged with religious studies, and then they married me to someone four months later. The so-called husband always beat me because I was a bit resistant, as I didn’t love him. However, food was sufficient. I ate good food throughout my stay at Sambisa, which lasted over 15 months.

BORN IN A BOKO HARAM CAMP

I was born in a place no child should ever call home. Boko Haram held my mother captive, and I came into this world in the middle of fear, hunger, and violence. I never knew what it meant to play freely or sleep without hearing gunshots. When the soldiers rescued us, my mother wept with joy, but I did not understand.

I JOINED BOKO HARAM. I DIDN’T HAVE A CHOICE.

My life took a drastic turn when I joined Boko Haram in 2015. Before that, we were displaced from Bama in 2014 and sought refuge in a village near Cameroon called Jimia. When our village normalised, and people began to return, we received alarming news: we had been declared Boko Haram members, despite it not being true. The place we stayed was considered a Boko Haram camp due to their frequent visits, and we feared for our lives.

I DESTROYED LIVES AS A BOKO HARAM MEMBER

When we went out on operations, I did things I can never forget. We would storm villages at night, armed with guns and fire. I stole from people’s shops, carrying away what they had worked for all their lives. We burned houses, leaving families homeless. We took food, money, and valuables from innocent people. Worse still, we killed those who resisted us, and I know many families are still mourning because of what I did.

I learnt from my interviews that Boko Haram is taking advantage of indigent people, telling them to join them, that they would provide whatever they need. I have also observed that proper provisions have not been made for rehabilitation. The government has claimed to have rehabilitated every repentant Boko Haram member, but I met with some who said they didn’t go to the rehabilitation centre. They came straight to the town and started living there. I talked to a woman whose husband is a repentant Boko Haram member working with soldiers. She told me they are currently planning to go back to Sambisa and continue living there as a family.

Military personnel still restrict people in many resettled communities from going beyond certain boundaries due to the continuing insecurity. Another challenge is that because these areas are not their original homes, they do not own the farmlands and can only work as labourers on someone else’s farm. There are still cases of attacks and abductions. Just recently, about 10 or 15 people were abducted in Dalori, very close to Maiduguri. It’s very bad. The people who were kidnapped are the people who just resettled two years ago, in an estate that the state government allocated to IDPs. Many of the resettled IDPs are leaving the state; they are going far away. Some of them are going to Lagos and Abuja, where they have some relatives, where they believe they will be safer and where they can go and work as labourers and find a means of livelihood. The youth are massively travelling out.

Currently, when you go to the resettled communities, there are visible signs of trauma. When you go to the villages, you will see some Boko Haram writings on the wall, some in Arabic. They will see those writings and psychologically they will be traumatised, because you will recall your relatives who were killed, the kind of people you lost, how you suffered. When you go to the communities most affected by this insurgency, you will see they are full of empty buildings. Some have not been renovated for people to settle there, and there are not enough hospitals.

Food production has also been very, very low. Because the men are often targeted for abduction, and women, especially those above 40 years old, now bear more responsibility for farming. Younger women are at high risk of abduction when they go to the farm. So, agricultural inputs are very scarce in those communities. Natural resources like petrol and fertilisers are extremely expensive there, too. There’s no single functioning filling station in Bama. It has been restricted by the government. Fertiliser is also tightly restricted because it could be diverted to make explosives. As a result, farmers now use organic manure, collecting cattle dung and spreading it on their farmland. But it’s not as effective.

— Usman Zarma.

WE THOUGHT WE COULD COEXIST

At first, when Boko Haram began entering our town, they told us civilians had nothing to fear. They said their fight was only with the government and security forces. They even came to the market to buy things without harming anyone, so we believed we could coexist with them.

WE’VE FORGIVEN THE REPENTANT BOKO HARAM

After we came back, NEMA started helping us with foodstuffs, but now they’ve stopped, and we’re not getting any support from anyone. Before we were displaced, our parents had farms and a lot of sheep, but the sheep were forcefully taken. Boko Haram took all of them.

WE LEFT ALL OUR BELONGINGS BEHIND

Boko Haram came with their guns and chased all of us away. Not a single person remained. We had a population of about 1,000 people, and we were all forced to flee with our children… Right now, we are in a critical condition due to the lack of proper accommodation. Some people fled but couldn’t reach Maiduguri; they are sleeping on farms, hiding among the trees.

WE LOST OUR LOVED ONES, HOMES, AND LIVELIHOODS

All our valuables, including our farm produce, were left behind. We used wheelbarrows to transport our younger children and essential items, and it took us two days to reach safety. We had to survive on minimal food during those two days in the forest.

WE ARE SURVIVORS AND WE’LL REBUILD OUR LIVES

Despite the challenges, I’m grateful for the support I’ve received. Organisations like Plan International have provided me with the skills and resources I need to rebuild my life. I’ve also received support from my community, which has been a source of strength and comfort.

I COULD NOT RAISE THE ₦500k RANSOM

After the deadline passed, we lost contact with my husband. Some of his fellow captives returned home a week later, but he didn’t. It’s been a year since his abduction, and we have no idea if he’s alive or dead. The returned captives told us he was left alive when they escaped, which gives us hope for his return.

THEY CUT OFF OUR EARS WITH KNIVES

They came with 40 vehicles, but I don’t know the exact number of soldiers they came with. They took 42 of us to Dalwa, tied us with a rope, and started beating us. They cut my ear; the CJTF cut our ears with knives — five of us. From there, they took us to Giwa Barracks in Maiduguri; we stayed for one week. Then they brought us out and asked us, “Are you Boko Haram?” We told them, “We are not Boko Haram; we are poor people, farmers, and animal rearers.”

THREE OF OUR PEOPLE DIED FROM TORTURE

They cut my brother’s ear and stabbed him in his ribs, and I took him to the hospital in Giwa Barracks, and he was treated; he even fainted. Three people among us died at Giwa Barracks due to torture. We don’t know anything; our time was just wasted. We used to be self-reliant.

HUNGER IS A CONSTANT COMPANION

Sometimes, I have to swallow my pride and send my wife to beg on the streets just so we can get something to eat. It’s a painful reality, but I’m willing to do whatever it takes to feed my family. Seeing her come back with a few scraps of food or some spare change brings a mix of emotions – relief, shame, and desperation.

IT WAS LIKE AN UNENDING NIGHTMARE

They came with guns, bombs, and a message of hate. They wanted us to abandon our way of life and adopt their twisted version of Islam. But we knew that wasn’t the way of our people. We’ve always been peaceful, tolerant, and welcoming to everyone.

TERRORISTS ATTACKED MY SCHOOL. I KEPT TEACHING.

After the attack, I could not return there. The classrooms were abandoned, the blackboards left untouched, and the joy of learning was stolen. Our school library stood silent, with books gathering dust, as though knowledge itself had been forced into hiding. I sought a transfer to Bulabulin Primary School, just to keep teaching and to survive. But fear never really left me.

WE HEARD EXPLOSIONS DURING LECTURES

At times, we would begin a lecture and hear distant gunshots or explosions, forcing students to flee for safety … There were nights I went to bed questioning myself: “Is this worth it? Am I risking too much?” But each time, I reminded myself that education is the only weapon that can fight ignorance and rebuild a broken community. That thought gave me strength.

I REMEMBER THE UNIMAID MOSQUE BOMBING

It was a cool morning. I had slept late while preparing for an examination. Suddenly, a soul-shaking blast tore through the calm. The sound alone felt like it took our spirits away. From the second floor of New Male B hostel, we could hear and feel the vibration. The attack, carried out by a suicide bomber, targeted the staff quarters’ mosque. It claimed the lives of academics and their family members, leaving the university community in shock and grief.

A BOMB BLAST SHOOK OUR CAMPUS

Studying at UNIMAID hasn’t been easy. The insurgency has left deep scars on our education system, and the university has not been spared from the violence. I still remember the night a bomb blast shook our campus. We had to flee in the dead of night, not knowing what the next moment would bring. It was during our exam period, and the disruption made it nearly impossible for many of us to concentrate or even find a safe space to study.

LOST MY FOOT TO AN EXPLOSION

When I returned to Maiduguri, I saw many men like me who had lost limbs. Many turned to begging, but I told myself, “They took my leg, but they won’t take my dignity.” I began learning tailoring through a programme organised by an NGO in our IDP camp. It was difficult at first, balancing on one leg and trying to sew, but I refused to give up.

A STRAY BULLET SHATTERED MY SPINE

Before the insurgency, I was a skilled farmer, providing for my family. Now, I’m unable to work, and my family struggles to make ends meet. We’ve had to rely on aid from government agencies and non-governmental organisations, which is often insufficient and inconsistent.

I CANNOT AFFORD MEDICAL CARE FOR MY CHILD

I would have sold any property I owned, but Boko Haram destroyed the house I inherited from my father in our village. The few valuables I had left here in Maiduguri were also burned during attacks – including my car.

THE MORNING I LOST EVERYTHING

I remember leaving the akara still frying in the oil. I didn’t carry anything, not even my money. I just grabbed one of my children who was with me, and we ran as fast as we could. We didn’t know where we were going, only that we had to find safety.

FROM A PROUD TRADER TO AN IDP

A group of women had started learning how to sew traditional caps. At first, I watched them from afar. My heart told me, “Aisha, you have never done this kind of work. Can you really start now?” But my situation pushed me to try. I joined the training, and for the first time, I picked up a needle and thread.

I SMUGGLED OUT STORIES ABOUT THE WAR

When the Boko Haram insurgency began, my world changed overnight. The sound of gunfire and bomb blasts became part of daily life. Many of my colleagues fled, and some were silenced forever. But I made a choice to stay. My family begged me to quit saying, “Bashir, your life is more important than the news!”

People from the villages are usually afraid when you tell them their stories will be published and may be read by people somewhere far away, because they don’t want to get into trouble. These experiences have taught me patience, empathy, and the importance of building trust while giving voice to stories that matter.

One of my favourite interviews was with the girl whose education was sponsored by her grandmother. She did not give up. Even though they lived with Boko Haram members, this did not change her perception. She ensured her granddaughter was enrolled in school and did everything to help her realise her goal of being a medical professional. This stood out to me. Also, the young man who lost his leg to the bomb explosion. He did not give up. He did not beg on the streets. He runs his business, and the disability of having an artificial leg doesn’t stop him from doing what he wants to do. If people see what he is doing, they will appreciate that losing your leg or a part of your body is not the end of your world.

A lot of people think that people do not even exist in Maiduguri, that people do not live a comfortable or free life here. But when you come, you see something different. There was a time I visited Abuja for a workshop where I met a lot of people. Whenever I told them I was from Maiduguri, they would be like, Maiduguri?! Hia. Boko Haram. During my service year when I camped in Kwara state, the same thing happened. If I told them I was from Maiduguri, they would exclaim and say, Ah, do people still exist in Maiduguri?

People should please note that Maiduguri is a land that has freedom. Even though there is the insurgency, it does not mean there is a hindrance for people to engage in their day-to-day activities. A lot of people think that everything in Maiduguri is hard, and day-to-day activities are not going as they are supposed to. But with everything that has happened, with all the insurgency, we are still strong. We are still resilient. We still achieve what we want to achieve. As you can see from most of the stories, our people don’t give up easily.

— Amina Muhammad Ali.

Curated by: Amina Muhammad Ali1 & Usman Zarma.2

Edited, designed, and vibe-coded by: `Kunle Adebajo.

- Amina Muhammad Ali is a professional scriptwriter and multilingual jingle voice artist with a passion for storytelling, especially in Kanuri and Hausa. ↩︎

- Usman Zarma is an experienced freelance writer, editor, and researcher with expertise in conducting in-depth interviews, crafting compelling content, and providing accurate translation and transcription services. With a portfolio spanning multiple industries, he helps businesses and organisations tell their stories, capture valuable insights, and achieve their goals through high-quality writing, editing, and research services. ↩︎

KEEP UP WITH Chronycles on social media

We were sitting with my wife, waiting to eat before I would go and start looking after my animals. They came and surrounded our village, gathered us all, and asked our head if we were part of this village. The bulama said, “Yes, we are members of the community; some of us are farmers, and some are animal rearers.” They said, “We still don’t agree,” and then they took all of us to their boss. They brought us out of our house forcefully, separating men and women, and asked us several questions, like “Do you know any Boko Haram members?” and “When Boko Haram captured Chibok girls, did they pass through your village with them?” We said, “No, they didn’t follow this way.” We told them, “We don’t know anything; we are poor people.” Then they took us to their boss, who was standing somewhere within our village.

They came with 40 vehicles, but I don’t know the exact number of soldiers they came with. They took 42 of us to Dalwa, tied us with a rope, and started beating us. They cut my ear; the CJTF cut our ears with knives — five of us. From there, they took us to Giwa Barracks in Maiduguri; we stayed for one week. Then they brought us out and asked us, “Are you Boko Haram?” We told them, “We are not Boko Haram; we are poor people, farmers, and animal rearers.” After answering their questions, they told me to leave, and I heard some soldiers saying, “This is a villager, but look at what they did to him.”

They tied us up from morning till evening, then put us in their vehicles and took us to the airport, put us in a big airplane, and transported us to Niger state. We reached there during Isha prayer time; then they put us in cells, with four people in each cell.

In my cell, I was together with my friend Dahiru and two other people from Maiduguri. Dahiru died from thirst; he died in my presence after he had been asking for water. Thirty-seven people died for the same reason (lack of water). Three died before we went to Niger; they died at Giwa Barracks due to torture. The food they gave us was not enough, but we needed water more than food. Our skin changed colour due to a lack of bathing and dirt. The cell was dark and cold, and we were only wearing short trousers; we were disturbed so often by ticks that they didn’t even allow us to sleep at night. It rained heavily there.

Then the Red Cross came. They brought us carpets and provided each block with tap water. We were given two buckets and two-litre cans to fetch water and keep it in our cells. Some got sick due to the long time without water, and when they drank water, their bodies would start malfunctioning. Some died. Gradually, our food quantity was increased by the Red Cross.

I don’t know the name of the prison they kept us in, but we call it Niger Minau; I don’t know the name of the barracks. Some committee members came and told us that, by God’s grace, those of us who were not guilty would be released; they were not soldiers; they were wearing personal clothing. Then they sent us to court, checked some documents, and asked me what my mother’s name was. I told them, and I was declared not guilty. We stayed in Niger for 11 years. After I was declared not guilty, I stayed for six more years. Then the commander came, looking for people who came in 2014, and separated us from others. He asked for our numbers, and I told him mine was 5; he said it was correct. He asked all of us for our numbers, then told us to calm down because some people had been transferred to Gombe. He assured us that we would be taken too. Four hundred of us were later taken to Gombe; he told us we would stay in Gombe for nine months in Malam Sidi. Sometimes we would play football, and sometimes we would watch films. Then we were brought to Maiduguri, to Umaru Shehu Hospital, as free people.

Our relatives came and took us from there, and that is when I got the information that my father and my wife were dead. When we were captured, my wife was pregnant, and she gave birth to a dead child because of the shock and stress. She later died. For now, my only remaining relatives are my mother and our elder brother. He brought us to his place, and he is the one taking our responsibility. We have no home, nothing. When we were in our village, I had 30 cows and goats, some millets, and a farm, and now we have nothing. When I got married, I paid ₦100,000, and she’s dead now; her name is Fatime Inneru. And now getting married is not easy; it will cost almost a million.

What we need now is help to become independent. We don’t need to beg. But now, from clothing to food, we only depend on someone to get it. We came back just four months ago; when we came, many people shed tears. We want to be self-reliant; we want to take care of ourselves.

We stayed for one week in Giwa Barracks and stayed for 11 years in Niger, and did nine months in Gombe. When we were in Niger, even to ease yourself, you had to seek permission, but now we can do whatever we want freely.

What we suffered the most in Niger was the lack of water. We could go for four days without getting water. They gave us tea in a small cup every day; sometimes they gave us two small cups of tea. We would drink half first and then drink the other half later in the morning. That is the time we suffered the most; that is when our people died. I could not even stand on my feet. The guy who was helping me is in Gombe now; they will be the next batch that will be released.

When we were in Niger, I saw some of our people before they died, but not all, because our cells are in blocks, and it’s a story building. I could see the block that was below our own; that’s how I got to see them. And sometimes, when they took people to the upper floor, they passed our block; that’s how we got to see some of them. And sometimes, they used to come and ask me, “Do you know this person?”

Among the 42 of us that were captured, only five of us are remaining; the rest are dead. I saw six dead bodies among those that we were captured together, but for the rest, we just heard their cellmate saying, “So-and-so person is dead.” The five of us who were still alive were eventually kept in the same cell, and among us, only three were released. The remaining two told us that when we get back home, we should please tell their people about their situation. Their names are Isa Usman and Maina Musa; they are older than me. The wife of one of them is in Dala; she came here and asked me where her husband was. I told her he’s alive, but he’s still in Niger. And the other one’s wife has married another person.

I am currently suffering from heart pain; when I inhale, I sometimes find it hard to breathe. I sometimes find it hard to eat. This is my major problem, and my other problem is the lack of self-dependence.

When we were about to leave Niger, everything was becoming enough; it had been standardised by the Red Cross, and I got some treatment when I was in Gombe. Currently, if I’m asked where Niger is, I don’t know because the views were blocked when they transported us.

I was taken to Niger with my friends, and they are all dead. We are now gradually getting friends, and sometimes we feel shy to be amongst people, to mingle with people.

We have nothing.

As narrated by: Mohammad Garba (Maiduguri, Nigeria).

This snippet is published as part of a series, The Day Boko Haram Attacked.

I was directly affected by Boko Haram’s abduction when they took my husband, demanding a ransom of ₦500,000 that we couldn’t afford. They gave us a one-week ultimatum to pay, threatening to harm him if we didn’t comply. We tried everything to raise the funds – visiting friends and family, begging on the streets – but we could only gather ₦150,000. The kidnappers refused this amount, insisting on the full ransom.

After the deadline passed, we lost contact with my husband. Some of his fellow captives returned home a week later, but he didn’t. It’s been a year since his abduction, and we have no idea if he’s alive or dead. The returned captives told us he was left alive when they escaped, which gives us hope for his return.

My husband was a farmer, and his abduction has left us in a desperate situation. I’m now caring for our six children alone. Life is incredibly tough; we often go without food, and the children were forced to drop out of school due to unpaid fees. We were displaced from our community, lost our livelihood, and have no assets left to sell for his ransom. The trauma and uncertainty continue to affect us deeply.

We reported our situation to our community leader, who promised to forward our plea to the government. However, we’ve heard nothing since then. We’ve been left to fend for ourselves, struggling to survive without any support. The children are suffering the most, missing out on their education and a stable home.

Despite everything, we hold onto the hope that my husband will return home one day. We’re doing our best to stay strong, but it’s getting harder each day. We need help, not just for my husband’s safe return but also for the well-being of our children. We need support to get back on our feet, to rebuild our lives and provide for our family’s future.

The impact of Boko Haram’s activities has been devastating for our community. Many families have been affected, and we’re all struggling to cope. We need the government’s attention and assistance to address this crisis. We need protection, support, and resources to rebuild our lives and ensure our children’s future.

We’re not giving up hope. We’ll continue to pray for my husband’s safe return and work towards a better future for our family. We hope that one day, we’ll be reunited, and our lives will return to normal. Until then, we’ll keep holding onto hope and striving for a better tomorrow.

As narrated by: Ya Indi (Maiduguri, Nigeria).

This snippet is published as part of a series, The Day Boko Haram Attacked.

I was in Nigeria in 1983 when Nigeria was good. I hustle for Nigeria for almost three years. I go do mason. Mason no good for me, I ran, go do electricals. I don hustle. I be hustler o. I ran from school; I ran from final year go Nigeria. That time, hungry dey Ghana. I was a victim of the Ghana Must Go campaign. That time, Nigeria was sweet. I worked in Apapa. My senior brother’s friends were living there. They were graduates, so they taught in Nigerian government schools. Nigeria was good. All my siblings stayed in Nigeria for so many years before they left for the US. That time, they were young. No be today Nigeria o.

The taxi business is very good. At first, I was working for a hotel. I worked as a shuttle driver for 15 years. From all my entitlement for 15 years, I couldn’t even save 2000 cedis. So, I decided to work on my own. A lady bought me this car, a lady. You do work and pay. She bought it 40,000 and gave it to me 80,000 for three years. I decided to pay it off before the three years. I work both day and night. This is my chamber or self-contained, I sleep inside. I do everything inside. I no dey go out. I used two years and four months to pay the 80,000. I finished paying last year. How did I celebrate? Still, the pressure is there, so how can you celebrate? I have children in the university. My firstborn finished just last month. And the other one is in level 300. So, you have to work hard.

All my customers are foreigners because I always treat them good. The majority of them come from outside Africa. When they are coming, they just call me. “Smith, we are coming. We need this car.” I will go and rent a car. Then I will use maybe two weeks or one week. A lot of the Black Americans come to Accra for holidays. They just come and go. Some buy houses here. Even tomorrow I have some coming, I have to pick them up from the airport. Ah, some of them are from Nigeria. They told me directly that they did DNA and they said they are from Nigeria, but they decided to come to Ghana. I say why. They say no, no, no. They say Nigeria is a very bad country, there is no peace in Nigeria.

If you have small money, you can rent police escorts. You know, those Black Americans, they have money and can pay. They will escort me, everywhere I go. I will pay them. It can be 100 dollars per day. You know, in their country, they won’t get those things. They will do video, show their friends, that they are doing convoy.

Ghanaians love foreigners more than ourselves. If any Ghanaian sees a foreigner, they become happy. They want to treat you special. You know we have a lot of Nigerians here. A lot, especially the ladies. Small small girls – 12, 14, 15. This evening, I will take you there. You will be shocked. They are the ones doing sex work in Accra here. If you ask them, 80 per cent are Nigerians. Some of them are underage, seriously. And they get money. They charge 100 USD and you know 100 USD per night is big money for Nigeria. If they [the traffickers] brought you here, after you pay them finish, then you be on your own.

Life, e no be easy o, bro. As you guys are young, you have to work hard. Me I said I don’t want any of my kids to suffer the way I suffered. No, no, no. That’s why I am giving them good education. My first-born studied Natural Resource Management. And the second girl is in level 300 at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. She wants to be a lawyer. I’m fighting hard, seriously. Because life is what you make it. I just want to make them happy. I’m getting old. Next week, the 18th of October, I will be 60 years old. Could you believe it? But nothing shows, right? I will advise you. If you are not married, just sit down and plan well. You know, women, all of them, their mother is one. If you don’t have money, it is a problem. But if you have money, you become a champion. Man has to suffer to take care of woman.

As narrated by: Smith (Accra, Ghana).

Photography by: Al’amin Umar Marte & Mansur Ibrahim.

Teachers are bound to leave when we consider how the government treats them. There is no doubt about that. Nigeria is one of the African countries paying teachers the poorest remuneration. As a result, many fresh brains are unwilling to join the train, while those already in the profession are desperately looking for means of escape. I was speaking with a friend today, who told me that the number of Physics teachers in the system is gradually dwindling. Those who actually studied Physics don’t want to remain. Some of them are travelling out.

There is no nation that can grow above the quality of its education, and no educational goals can be achieved without quality teachers. Teachers deserve to be adequately remunerated, planned for, and given a sense of security. A situation where state and federal governments struggle to pay gratuity ten to fifteen years after retirement is not just insensitive but criminal, a situation where the contributive pension schemes are tampered with, and a lot of yearly incentives are delayed or denied. It has forced those who should be resting to continue labouring.

The critical aspects of schooling are either missing or falling apart. A lot of schools don’t have counsellors. If not a hundred per cent, I guarantee you that that section is 95 per cent dead. There were days the counsellors were always ready, always there for you, asking you to come for interactive sessions and all that. But that aspect is practically dead. Will it bother you if I tell you that recently I had an encounter with a group of students and I asked them why they were going to the Humanities Department? The first answer that one of them gave was what the other six mentioned. He said he wanted to become an artist, to draw. Apparently, he happened to be the only one who had a background of why he wanted that department. Others simply copied what he said. They had not thought of it. They just felt, let me go to that department jare. There is no orientation, no counselling.

There are a number of things I don’t regret. But sometimes you think, after all this, after all this commitment, is this what you are getting? One is bound to feel, ohh, maybe I should have dissipated this energy on something else. But, well, certain things give you joy beyond money. I have seen instances. So, it’s okay. We’ve paid our dues. Now, it’s to open up our brains to make sure that when this energy starts failing and the strength is no longer there, there is something to fall back on. Today, I’ve been to two tutorial lessons. It’s because the energy is still there.

Sometimes, when I see those who are older than me, those who were even practically my teachers, still struggling with us when we want to mark external examination scripts, I don’t feel too happy. Don’t tell me it’s because of experience. Don’t tell me, ‘I don’t want to just stay at home.’ I don’t want that excuse. If you’re okay in the real sense of it, you wouldn’t bother. The day I saw one of my students come to mark, the reality dawned that we have also aged. So, imagine, while lining up to collect papers, we are pushing ourselves and struggling with our students. People give a lot of excuses for why they do it. Some will say for experience. Forget experience, nah money you need. It’s unavoidable when those who have worked for years are denied their rights.

It is unfortunate that in Nigeria, what teachers are paid is not in any way in tandem with the hours they give. That’s just the honest truth. For example, in Ogun state, teachers are not earning the current minimum wage. When the federal government removed the subsidy and said they would increase the minimum wage, before they did all the paperwork, the president promised the payment of ₦35,000 palliative at the federal level. I think Lagos state complied. Ibadan, I think, was paying ₦25,000. But teachers in Ogun state received ₦10,000. So, the government of Ogun paid ₦10,000 for nine months, then stopped. Now, do you know that in the Federal Government, right now they are getting arrears of that ₦35,000 and they have effected the minimum wage. What reason does a government have for adding ₦42,000 or thereabout across board for civil servants while the workers patronise the same markets with others earning the minimum wage?

Teachers are resorting to extra laborious tasks to make ends meet. It is as bad as taking tutorial classes for a paltry sum of ₦1,200 per hour. This is what many use to augment the poor remuneration.

Imagine one spending approximately ₦60,000 monthly on transportation out of the net payment of ₦162,000. What of feeding, healthcare, marital responsibilities? And you still have to pay back debts, whether shark or crocodile loans. At the end of the day, what I receive monthly is ₦80-something. Which means, practically, that the salary of teachers in Nigeria, especially in Ogun state, cannot sustain the workers. Imagine the daughter of … a colleague asking her father, “Why don’t you have money?” That’s a very big question. Why won’t you have money? Even before she asked, you would have been going through silent torture, worrying about what your family would eat.

We are thanking God. We are thanking God. We are thanking God. We will surely get there.

A lot of brains have left the profession for countries that value their expertise. People speak highly of Oman. The pay is good and the hospitality is higher. They take lots of teachers. Unfortunately, there is a religious bias. A friend over there told me that his apartment was flooded because of an overflowing tap. If you know how much they gave him as compensation, and they still apologised. They told him sorry. Does the government know whether you exist here in Nigeria?

As narrated by: ROTIMI* (IJEBU-ODE, NIGERIA)

My artistic journey can be traced to my childhood experience, growing up on the streets of Iwaya, in the Makoko community of Lagos. When I was in my formative years, Auntie Motunrayo Abayomi always organised summer coaching classes for us that lasted for two to three weeks. We would have a cultural presentation on the final day. She taught us topics outside our primary school curriculum, including different songs that we would present to our parents wearing cultural attire.

When I entered secondary school, I was a commercial student. I really wanted to become a banker or an accountant. So I enrolled on commercial courses. My mom sold pepper. My dad was a real estate agent. Unfortunately, I lost my parents in 2009 and 2012, so I was going through a lot.

I worked for a telecommunications consulting company between 2016 and 2017 as an admin person and cleaner. It wasn’t going so well, so I decided to resign. I wanted something new. I was tired of working and getting ₦18,500 as salary. It couldn’t sustain me anymore. I wanted more. I had been exposed to different kinds of life. Going out to art events, seeing people … I wanted to seek more.

In 2018, I saw a post on Facebook that a group was organising a one-year art school programme in my local community. So I was like, I think this would be a good opportunity for me. For that one year, I wasn’t working, and there was no funding. I didn’t have parents catering for me.

After we finished building the space, we commenced classes in art, watching YouTube videos, running performances and assignments. During that period, there was no money coming in. At the end of the programme, I asked myself if I truly wanted to become an artist. My kind of practice is quite interdisciplinary, where my art spans across performance installation, graphic, video art, and research. And research has been the source of my strength recently. It allows me to look back, reflect on my past engagements, and my history to create a form of artistic statement.

The pleasure I derive from being an artist is that I get to tell my story. I ask myself, would accounting give me the same opportunity? Would it give me that opportunity to create worlds that will give the next generation a bigger imagination? The pleasure I derive from this practice is the possibility that whatever I think about, I can create it, and people will surely resonate with that creation.

I’ve not had a 9-5 job since I quit my last one in 2018. The idea of a salary is not in my calendar anymore. What I do mostly is to use that period when I don’t have anything to reflect, to research, and come up with a winning and competitive proposal. I have been relying on grants since 2021/22, when I won a grant from the Goethe Institut to create my first solo exhibition titled Son of a Peppered Seller. In 2023, I also won a grant to create a social art project on the extinction of local food culture in urban spaces titled Jeun Soke. Towards December 2024, I won another grant that gave me the opportunity to create my last exhibition before getting this residency. This is my fourth residency opportunity and I like the fact that it is coming locally. It really helps me to solidify my practice.

There are moments of regret, sincerely. There are times I would need money, and I would have to borrow and then refund whenever I get funding or I get a side job within the arts. Times you just have to eat what is available, not what you want to eat.

There is a gap between the experiences of local artists and artists in other countries. Art practice in Western countries or in Europe is quite favourable because there are budgets, there are programmes that the artists over there can bank on, there are residencies and opportunities that the artists can leverage on because their governments consider them as part of the workforce. But over here, there’s nothing. Artists always look up to the Westerners, the Europeans, for opportunity, for funding to create work. So it is more of a struggle. The poor condition of artists is reflected in the studios. Most artists use their houses or backyards to create works. And there are no gallery representatives to mentor them. You have to take care of yourself.

I think the biggest challenge is funding. And the periods between getting funding can be a big challenge for artists particularly, because you are going to have a backlog of debts. You don’t have any salary, so how are you sustaining yourself if you don’t have a business you are running on the side to survive? So, there’s that anxiety where you just have to be looking up to God for an answer to that your proposal. I am talking personally based on my own practice. There are some artists, possibly painters, who, within one or six months, will surely have work to sell. But my kind of creations are not sellable, they are more of institutional projects, projects that help people acquire new knowledge about certain things.

We live in a digital community. What we see on Instagram is quite different from what the artist is experiencing. Most artists are going through things, but on their Instagram page, you will see a different picture. But there is this courage that artists always have. That ability to wait is something inspiring from the few artists that I know, that something will surely turn out for them.

For me, I have gone about two years without funding. You have to manage the little you have and look for other means of surviving. If somebody calls for an artist assistant, you have to go there to pay yourself and move on while you are still waiting for funding. Sometime last year, I worked as a coffee shop attendant, helping a friend manage his business, while waiting for funding. You just have to find a hustle. Working as a production assistant for fashion, films, and the rest.

Managing funding when it finally arrives is something difficult for me personally, because by the time it comes, you must have suffered for over six months. Your clothing, your bills, you have to settle that. You have to settle debts. You have to support your struggling friends. And also you have to think about the work, because the money is not for you to enjoy; you have to create the job and work with people. So at the end of the day, the funding will not even be enough to sustain yourself until the next one comes. I’m working towards other means of sustaining myself and sustaining a family. If possible, it can be more of a research thing or a business within the arts, you can use as a substitute till you get funding.

My target for the next five years is to build my portfolio, in the sense of having degrees and also building a strong institution around my practice. I am currently working on building an institution called the Centre for Food Culture. My art has been based on food and the rest, so I want to build a centre that serves as a medium of addressing socio-cultural issues such as hunger and food scarcity within local communities.

As narrated by: OLUFELA OMOKEKO (LAGOS, NIGERIA).

When I first saw my posting to the Port Harcourt campus of the Nigerian Law School, I reloaded the page, logged out and logged in again, hoping it would change. Port Harcourt felt too far, too unfamiliar, too not Abuja. But I convinced myself that if I got posted to Port Harcourt, then maybe I was meant to be there. It still bothered me that the city was far from home and that I didn’t know anyone there, but I tried to stay positive. I had no other option.

My family helped me feel better. They sent hostel pictures and TikToks of the campus looking beautiful. I also heard from former students that the lecturers were good and friendly. Apart from the cost of travelling, I started to feel lucky. This campus was only three years old. It couldn’t be bad, right?

It was bad.

Nothing works. The grasses are overgrown. The light is never constant; most times, we depend on a generator that barely runs three hours a day outside of lectures. Sometimes there’s more to do in class, but the generator goes off and it becomes hard to continue. Water isn’t constant; some rooms barely get running water. Students have to climb a lot of stairs to fetch from different places. There aren’t enough cleaners, so the toilets in class are always dirty. At least one out of three projectors in class is faulty every day. The microphones always need a mini CPR. I tell myself: at least the lecturers are really good. Maybe that’s all that matters. But delusion has a limit.

When my family members call, after “How are you?” the next question is, “Do you have water now?” Not “How is reading?” Not “How is revision?” Because in a place meant to prepare us for one of the most important exams, the struggle sometimes isn’t studying, but how to get water. I once spent three hours waiting by a tap. Waiting for the water to run. Then waiting again for my turn. That’s three hours I will never get back. Three hours I could have spent reading. Or at least resting. I spent it sulking and feeling so insignificant. I miss home.

The Nigerian Law School is intense. It makes you conscious of time. It makes you calculate what every wasted hour costs, and that makes the suffering hit harder. You are more aware of how this is wrong, but you can’t do anything. You can’t even sulk for long; you just have to bear it.

I had high expectations — noble profession and all that. I thought if lawyers were in charge of administration, it would be better than the average Nigerian institution. I was wrong. We are noble because we are taught to eat with forks and knives, to wear black and appear sober, but that’s where the bar is. We aren’t respectable enough for running water, constant light or a proper address. They won’t ignore a sleeve an inch too short, but they’ll look away when we carry water on our heads. Maybe this is what it means to be fit and proper.

What adds salt to injury are the questions from those in charge: “What state are you from?” “In your university, did you always have water?” “Do your Deans come to address you?” As if we are second-class citizens begging for too much and not here in an attempt to become lawyers, asking for the most basic things.

As narrated by: BELEMA KOKO* (PORT HARCOURT, NIGERIA)

If I knew someone willing to give me a job there, I would like to go to Canada. I’m interested in driving, though I also have an engineering background. I know the mechanic job abroad can’t be as strenuous as the one in Nigeria. You will only be replacing gears, unscrewing and rescrewing parts. But for Nigerian cars, you will work on them so much that all your hands will be dirty and scraping the floor. Tohhh. But when you travel abroad, you will wear a uniform. You will work, but you won’t even feel like you’re working. I have friends there. One friend is in Dubai, another is in London. I don’t know what they’re doing. We only know what they tell us when they visit Nigeria. Some could be washing corpses or cleaning up after old people in the toilet. But whatever they’re doing, it’s at least better than what we have in Nigeria. Ehn ehn. Tohhh.

I was working with my friends. But the government started restricting us, telling us not to stay in certain places, and that we (mechanics, painters, panel beaters) should all go to Power Line. But that place is crowded, and I don’t have charms. All those old people would target you. They would have poured something in your shop before you arrive, and you would not get customers. That’s why I switched to driving.

I have been working as a driver at the airport for more than 15 years. I own this car I’m driving, but it is on hire purchase. I’ve been thinking of leaving the country for a long time, before Buhari even got there, before it got this bad. I was praying for the opportunity. I have a friend who just learnt how to drive those 4-clave trucks. He said his brother abroad told him that is what is reigning now and gave him some money to learn. He got a certificate, too. Even if his driving is not perfect, they will retrain him when he gets there. I said, tohh, maybe when I am ready to travel, I will try to do that. Driving garbage trucks is another useful skill. But you need money to learn. I don’t have enough at the moment.

Everyone is tired of Nigeria. As we are making money as drivers, we are spending it back on the car. If you earn 30,000 Naira and spend 15,000 Naira on fuel, what then is your gain? Every month, you will service your car. You will replace your tyres. You will pay rent. You will pay your children’s school fees. You will eat. You will repair your car if you don’t want to start from scratch. You will pay the car owner. That’s why I think if I see the opportunity to travel, I will grab it.

The airport authorities are also disturbing us. They call somewhere a public car park, so anyone should be able to use it. But the FAAN authorities will disturb you, saying you have no right to enter. They might deflate your tyres for three to four days. You wouldn’t be able to work. I took a risk by staying by the gate to court customers. Because when passengers leave the airport area, drivers who do not register will be the ones picking them up. So what is the point in us registering? We register and pay for tickets. I pay to use the public car park, too. They gave us uniforms and we have our ID cards. We are not touts. We are not thieves. Why then are they disturbing us? They say because some old men say car hire should not enter. Maybe when they originally made that policy, commercial drivers were not paying and they were bargaining. Let people pay their money and leave. The place they assigned to car hire people, not all of us have access to it because we are many. They only invite us in when it is our turn, and it may take weeks. Will you now park your car at home for two weeks because you are waiting for your turn? When there’s nothing wrong with you or the car.

Sometimes, when I am coming to work, it’s one of the things I think about a lot, leading me to decide that it’s better if I leave the country. It usually perplexes me that they disturb me in a place where I’m not operating illegally. These are the things causing hardship for people. Someone leaves his house to fend for his family; he doesn’t want to steal. You have a car and you’re still hungry. What’s now the point of the car?

We used to have customers reaching out to us to be driven around for three to four days or one week, but we don’t have that anymore. That’s one of the things the economy has affected. Maybe they’re visiting the city for business and they don’t have a car, so they rely on car hire. You can agree that they would pay 60,000 to 70,000 Naira per day. Those requests stopped coming later during the Jonathan era, before Buhari became president. We had surplus work at that time. You will definitely see customers. Flight tickets were not so expensive. But now, it is powerful people who board planes. When some people disembark, they will start trekking straight to the express. They know when they get there, they will get buses that will take them from one stop to another till they reach their destination. People didn’t do that before. Everyone boarded the taxis with confidence. If you were going to VI, it cost 6,000 Naira then. Ajah, maybe 16,000 Naira, because fuel was affordable. Filling up my tank then only cost 12,000 Naira. If you go to a station with a fair meter, it would be 11,000 Naira maximum, during the Jonathan administration. Now, going to Ajah, the fare starts from 40,000/45,000 Naira, because the fuel for that trip would cost up to 15,000/20,000 Naira. Tyres used to be 5,000 Naira. Now it costs between 25,000 and 35,000 Naira. But we have to keep hustling. There is still money in Lagos because there is business. It is only if you don’t step out of your house. When you come out, you will see a little to keep the body together.

As narrated by: LATEEF (LAGOS, NIGERIA)

I would say I’m not a full-time filmmaker. My last film was released last year. Before that, it was 2021. The film I made in 2021 is a feature film. It’s making money, currently on Showmax and African Magic. The amount of the money is another discussion, though. With the way distribution goes in Nigeria, you can’t really rely on it. It’s one of those things that you just kind of stack up a lot of IPs and they would be bringing money. The approach I’m trying to have is to own my time and do a lot of things that can make money while I’m living my life. Like right now, I sell a lot of stock footage. I create it once, I do metadata, and as you increase the number of assets in your portfolio, earnings increase, and it becomes reliable. That’s my ideal lifestyle. Basically, creating stuff and using it to make money. The other way I make money is through NGOs. We currently have some agreements and if they like you, they get in touch with you and things happen. There are some months when the work is stacked and you just manage it as you go.

I worked full-time from 2018 to 2020. I finished uni in 2015, did NYSC, and went to film school. Then I found this work opportunity at an NGO. It’s crazy thinking about what they were paying us. I think I was mostly there just to please my family. When COVID happened and funding priorities changed, they were going to let us go. But for me, just as a commentary on how shitty the pay was, I resigned. I told my family they let us go. For a while, as long as what I was making was more than what I was previously paid, I was like, yeahh, I’m alright. It has just kind of picked up from there. My take-home salary then was 124,000 Naira, and they wanted to be your only business, on top 124k! It just did not make sense.

My mom’s generation, they are the ones who could stay with one job for 30 years. But the world has moved on from that. In my 9-5, they gave us an annual leave of 22 working days and at Christmas, they shut down for the year and deduct like nine of those days from you. I’m not the one who asked you to shut down, so now I have to manage 13 days. And those 13 days, I can’t take it at once. You are told, Okay, for the first half of the year, you can take one week. I was thinking, this is not life. Three months into the job, I had seen them finish. COVID year, I was trying to leave in April. I stayed till September because again, uncertainty. Let me just be collecting the paycheck. The HR person that came up with that thing, only God can judge them. Employers should plan their affairs, so that people can have a life and take breaks.

The way the skydiving started: I was in the second or third year at the University of East Anglia and there was a skydiving society. A friend and myself were interested in getting our licence, so we joined the society. For some reason, that year, the committee was the most ineffective. Basically we paid our membership fee and the ball didn’t get rolling at any point. We were very disapppointed. During the summer holiday in 2015, my cousin and I were not back to Nigeria yet. We found like three spots in the UK where you could skydive. The one we went to was somewhere called Beccles. At this point, I had zero experience, so it was going to be tandem. All you need to do is be attached to somebody and just do what they tell you and you’ll be alright. The plane is narrow, so from one door, everybody scoots to the back. Because of this, the last person to get on is the first to jump, and that was me. They reassure you that there is a backup chute and there’s hardly ever any accident. It’s not as scary as you think. The instructor attached me to himself and we started scooting to the front of the plane. They opened the door and for a good 20 or 30 seconds, I was just suspending from the plane while the guy’s ass was at the edge of the door. You are supposed to do some kind of superman pose, so that aerodynamics can work in your favour, because you don’t want to spin out of control. You have to take formation. I was just hanging with my thoughts. You free-fall for maybe 30 seconds to one minute. For the first 15 seconds, I closed my eyes. I didn’t want to see. When I figured out I was alright, I then opened them and enjoyed the view. After that, it’s just something you want to go to different locations in the world and do, you know. Because like skydiving over the Palms in Dubai is different.

I think over time, you just see risk-taking as being a bit more fruitful. Sometimes, you’re going through stuff and then you feel like the world is against you and things can’t be figured out or something. For me, I kinda just saw everything as small, and I guess the kind of mentality the experience gave me is that everything is about perspective. Depending on how you look at stuff, you can make it big or small. Moving off from that, I just resolved to be like, if something is not life-threatening, there is no reason to stress over it. I felt empowered. It just gave me the confidence to do stuff afraid. After that, I’ve done scuba diving, I’ve done abseiling – going off the edge of a cliff with rope… all scary stuff. I don’t think I did any crazy thing before this.

Being in Nigeria has definitely suffocated my desire for adventure. I took some opportunities when I was in school. There is one time me and my cousin had Schengen visa because when you apply from any other country, they are a bit more open-minded — they are looking at the economic situation in Nigeria and thinking you’ll run. I had the visa and travelled to like four other countries. I took the bus to Wales, flew to Ireland, flew to Belgium, took the train to Paris, and train to London. Some months later, my cousin and I decided to go to Germany. We were there for like 48 hours. We landed in Munich, visited the Mercedes Benz museum & Porsche museum in Stuttgart. We also drove 600 km each way to Berlin and back, testing the highest speeds we’ve ever known on the Autobahn. From that experience, you get what German machines (Benz, BMW, Audi) are made for. We visited a section of the Berlin Wall, the Brandenburg Gate, and all that. Since I got back fully in 2017, last year was the first time I would get Schengen tourist visa from Nigeria. It was crazy. At some point, you’re just kind of defeated and resigned to fate as a Nigerian. Last year, I spent a lot of money on visa applications. Before I got the French one, I applied to Portugal. I did an appeal because they didn’t have any basis to deny me. I’d held multiple visas, I always left on time, and had all the supporting documents. When you’re unemployed with no assets, they tell you you’re unemployed, you don’t have money and you’ll elope… but then you have all these things. I’m like, I have this history, dude. I’m going to come back to my country. I’m telling you I have ongoing work agreements with these people, I’ll be back to continue the work. It’s just not fair. My moonshot is perhaps to purchase a new passport. Too bad that all of them recently hiked the prices. How much can you even do while in Nigeria? You want to go to Ikogosi in Ekiti, there’s bad roads, so many hazards and you might be kidnapped. Throughout my road trip to Ghana this year, the only flights I took were within Nigeria – the flight to Lagos – because of the stress and drama on Nigerian roads.

Anyhoo, I’m not slowing down anytime soon. I plan to keep exploring God’s green earth, experiencing humanity, discovering delicacies and speaking foreign tongues. You might even get lots of travel content and artistic expressions from me, but in the meantime, let me get over my millennial tendency to hoard content.

As narrated by: SELE GOT (ABUJA, NIGERIA)

I

I joined my partner in Toronto at the beginning of winter, when there weren’t a lot of activities for someone coming from a warm climate. It was difficult to make new friends, explore places, or do my favourite activity: cycling. My fingers froze over multiple times as I accumulated gloves with varying promises of protection while cycling. I tried to stay active with my partner: we used our home gym, we went on long walks, and as soon as we cracked our first few friendships, we basked in the opportunity to have familiar people to jolly with. Our friends are really kind people who share many of our values. It might seem mundane, but finding someone to play FIFA (now EAFC) with is a thing of joy. I don’t know why people still play PES.

When I was an undergraduate, I volunteered a lot and that allowed me to travel to different parts of Nigeria, meet people across different social classes, do things for people I may never meet again, and find joy in community. Even as I have lived across multiple cities in the past few years, I have learned to always find communities that fill my life with joy and satisfaction. Like missing the sun when it starts to snow, a hole grew in my heart for the noise of a community of which I belonged, after moving to Toronto. I did not want to be defeated by the isolation and loneliness that many newcomers complain of, so I promised myself to fight pretty hard to meet people, make more friends, and be part of communities again.

About three months after my relocation, I saw a shout-out — on a local newsroom’s newsletter — to an organisation that had cyclists volunteering to pick up food and other resources from food banks and other places and people giving out stuff to be delivered to the homes of those who needed them but who couldn’t go and get them on their own. I signed up because it combined my favourite activity with my curiosity for people and places.

I couldn’t pick up deliveries for another month because I had to travel for work. When I eventually made my first delivery, it started snowing out of the blue and I was caught in it. The second time I delivered to someone, it was to an elderly woman who refused to collect the supplies directly from me, and I had to put the food outside her door. It bothered me a bit that she might have been racist, so I spoke to my partner and some friends about it. After yapping about the situation, I decided she was just an old woman who didn’t want to stress me, but I made a note not to sign up for her supplies anymore. I have been to her apartment complex many times after that, delivering to other elderly people in the building, like the old catholic woman who prayed for me for a minute and kept thanking me for helping her out, being patient enough to wait a long time for her to open the door, and helping her move the supplies into her kitchen.

II

I meet many people when I deliver supplies. I meet a lot of kind, grateful people. I met a disabled gentleman who asked that he take me around Toronto if I was up for it, after learning that I had recently moved from Nigeria. I didn’t follow up because I felt I would be stressing him. I have a family that I have signed up to deliver supplies to for as long as the food bank is open, because of how kind they are to me. That I know their allergies and preferences makes me feel happy to ask for supplies for them at the food bank. I have also had very strange occurrences. Like the woman with a dangerous dog warning on her apartment door, whose dog barked so ferociously that it struck fear into my heart. It was the first time I didn’t wait for more than a minute for them to get to the door.

There was another strange occasion where I got to an apartment complex and ran into this weird-looking man who kept staring at me. He would give me a jumpscare in the apartment’s dimly lit corridor just before the elevator. I would enter the elevator fully alert and ready to defend myself with force if necessary, when he started talking to me. It was Eid day, and during our short conversation, I would learn that he was from Kenya, and I had been to his homeland more recently than he had. He would walk out of the elevator, leaving behind an ominous message: “Be careful out there.”

Apart from delivering food, I have also found a community with a group of cyclists training for a fundraising event. I had gone out to train some Saturday morning when I saw this army of lycra-wearing folks. I asked if I could train with them, and they were happy to have me.

This group has taught me a lot about caring for other people, and caring for myself. There is an older man, let’s call him SY, who helps to train others. SY is at least 60 years old, charming, helpful, and dedicated. The summary of what I have learned from SY is that being the strongest should always condition you for kindness. Despite being the best climber — climbing is such a difficult thing in cycling that not all pro cyclists are great climbers — SY makes an effort to train others, wait up when he can, and push people to be better, stronger and healthier.

From August 3-8, 2025, I will be spending five days on the road with this group to cycle 600 km from Toronto to Montreal, to raise money for people with HIV/AIDS. As a first-year rider, I am trying to raise CAD1,950 to participate in the event. People from around the world have been kind enough to help me raise CAD1,076.56 as of writing this. I still have about CAD900 to go, and if you’d like to support me, you can do so here. All proceeds go to getting food, clothing, shelter, healthcare, and other support for people with HIV/AIDS. None of the money comes to me.

Friends for Life Bike Rally

This rally is my way of showing up. For others. For community. And for the version of myself that believes in pushing forward, one pedal at a time.

III

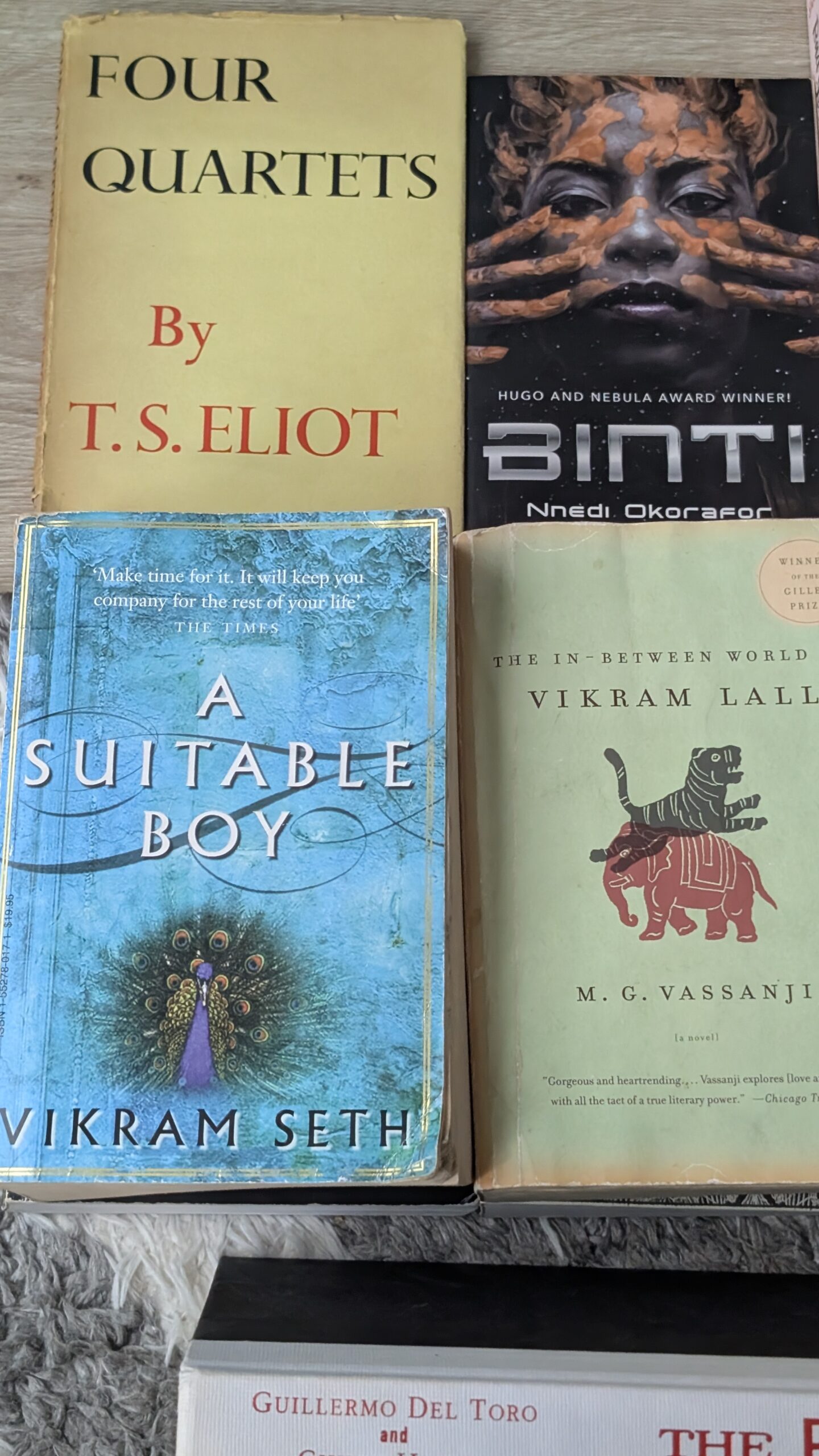

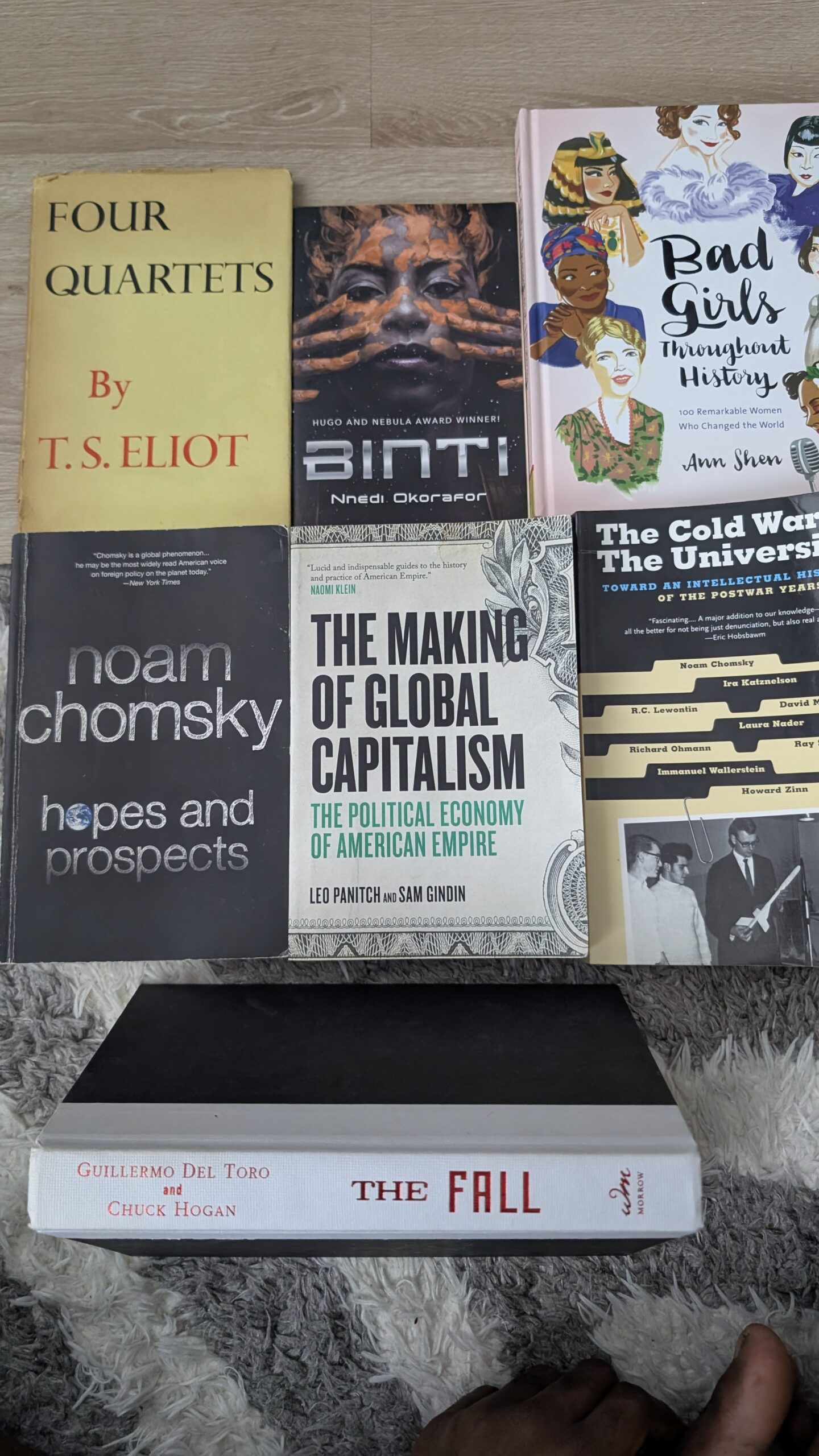

My friends and I went to a very rich neighbourhood for a yard sale. We got to a house with a shit load of books on women’s rights, socialism, workers’ rights, and some very rare English works. Saw some early edition T.S. Elliot. We asked folks around how much the books were. They said they weren’t sure, but they thought they were free. We decided to wait until we saw the owner and asked them ourselves. Barely two minutes after waiting, a lanky old man came from the backyard, eyes sunken, hair greyed with bald patches, holding gardening tools. He told us the books were free to take. It was a pretty conservative and Jewish neighbourhood, so it was unusual for someone to have that many liberal materials just out on the porch. Some of the books we saw were anti-zionist, pro-peaceful Middle East. We asked the man about his interests, how he came to have such books and why he was giving them away.

Old man invited us into his home.

We had a rich conversation about anti-semitism, his family, zionism, Palestine, the state of the world, his life, etc.

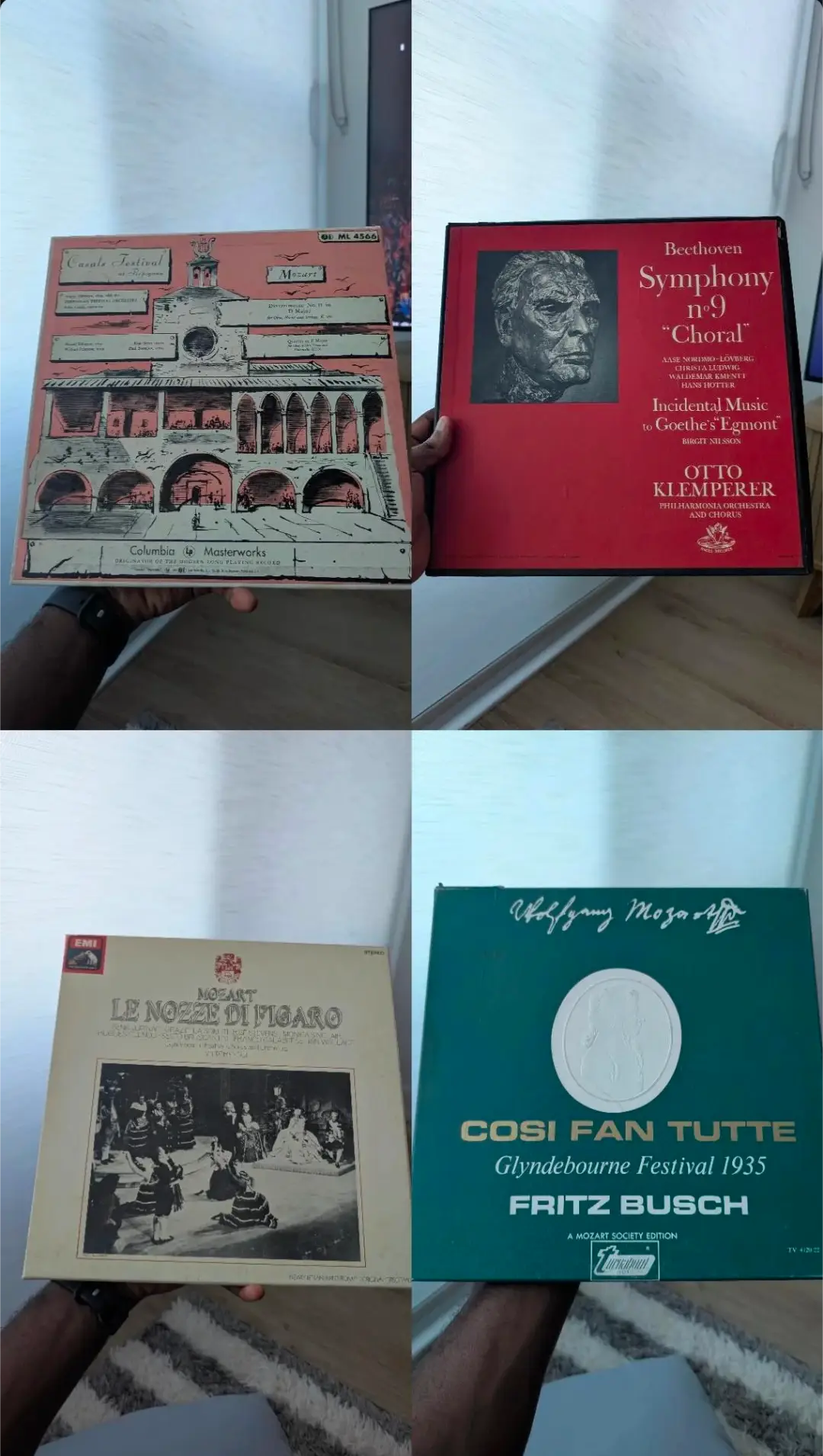

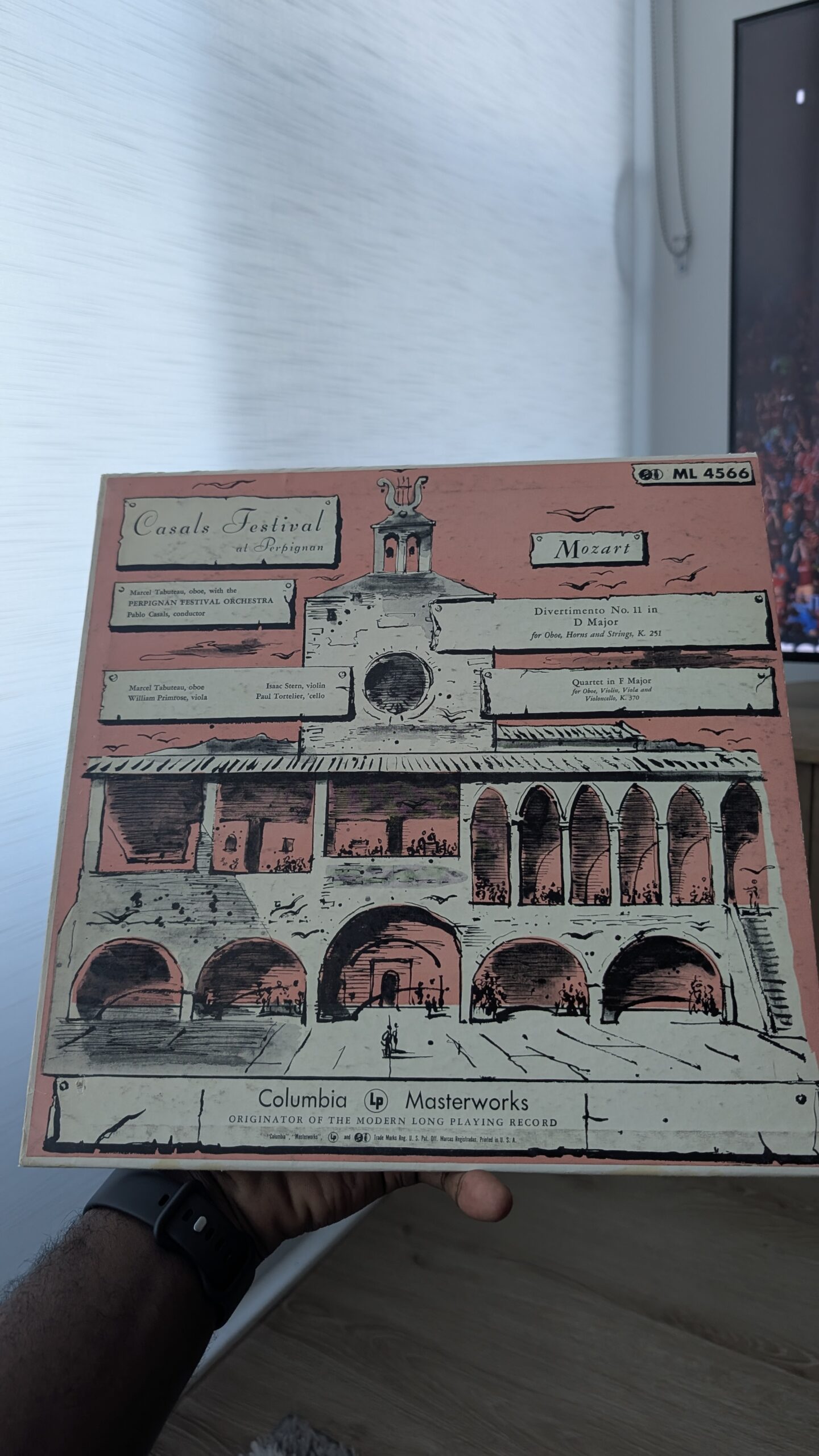

In his home, we saw an even larger collection of books and classical music. Old man is a musician in a long lineage of musicians. He had these classical collections at home that he was trying to give away. Some, he said, had been in his family for more than 50 years. He gave me a Mozart that his (deceased) wife inherited from her father. He let me have a tennis racket that his wife got when she started learning to play as a teen.

We live in a deeply beautiful world where my family from Nigeria gets to keep the multigenerational story of a liberal Jewish family from Toronto. A world where I get to deliver food to people as a way of knowing Toronto and people beg to cook for me with their limited supplies. A world where I could be asked by a stranger if I wanted some shoes on the same elevator where I was stared down by another stranger. A world where I get discounts for fixing my bicycle because I am fundraising for People with HIV/AIDS, despite someone driving their car over my foot at a traffic light.

There is so much beauty in the world that we live in. And it saddens me that despite this beauty, despite this grace, we also have to endure harsh unkindness.

But I’ll always choose to hold on to the beauty. Because more than anything else, beauty endures. Beauty heals. Beauty makes for a good world.

I want to live in a good world.