I was born in a place no child should ever call home. Boko Haram held my mother captive, and I came into this world in the middle of fear, hunger, and violence. I never knew what it meant to play freely or sleep without hearing gunshots.

When the soldiers rescued us, my mother wept with joy, but I did not understand. To me, freedom was strange. I thought maybe life outside would finally mean peace. But when we returned, a new kind of suffering began.

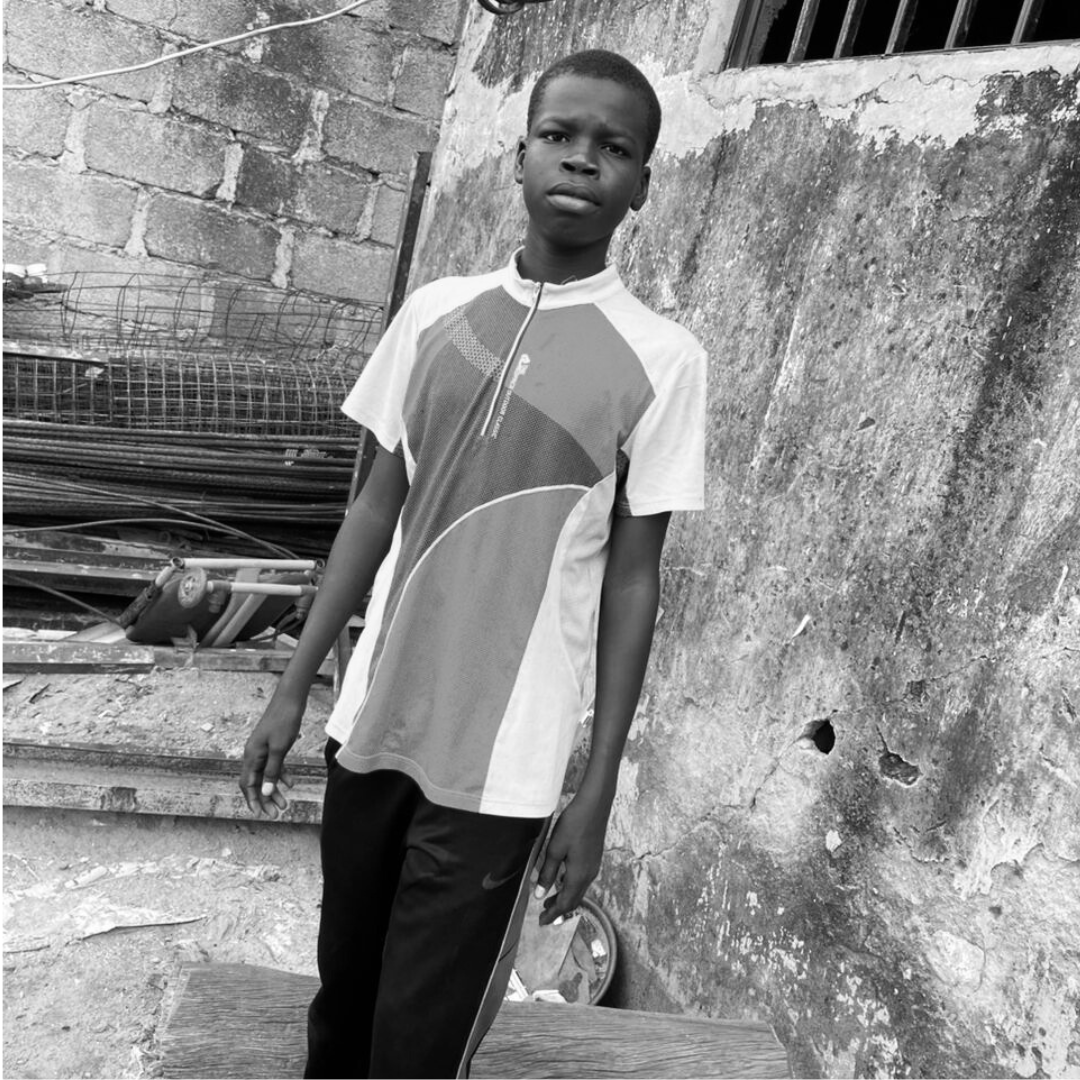

The children in the village refused to play with me. They called me “Boko Haram’s child.” Some parents told their children to stay away, as if I carried a curse. At school, I sat alone. At home, I heard the whispers. I used to ask my mother, “Why do they hate me for something I did not choose?” She would hold me tight and say, “You are innocent, my son. You belong to God, not to Boko Haram.”

At school, I was never just “Ali”. To many of my classmates, I was “the Boko Boy”. The whispers started as soon as I walked into the classroom. Children would exchange looks, some shifting their chairs away, others giggling as if I carried something contagious. They didn’t want to share books with me, and whenever the teacher paired us for group work, I always ended up alone, staring at the empty seats beside me.

I used to ask myself a lot of questions. One day, we were asked to work in groups for a mathematics assignment. I waited, hoping someone would call me over, but once again, no one wanted me. My eyes burned, but instead of walking out, I pulled my book closer and began solving the problems on my own. I worked harder than I ever had, determined to prove that I was more than their whispers.

When the teacher collected the papers, she studied my answers carefully. Then, in front of the entire class, she said, “Ali’s work is excellent, better than most of your groups. This should teach you all that a child is not defined by the mistakes of his parents.”

For the first time, the classroom went silent, not with mockery, but with surprise. Some of the boys who always teased me avoided my eyes. A few others, curious now, sat closer to me the next day, asking how I solved the questions.

It wasn’t as if everything changed immediately. The stigma did not disappear overnight, and there were still whispers and the occasional cruel word. But slowly, a few classmates began to see me differently. They started asking for my help with homework, and sometimes even invited me to join their games during break time.

That was when I realised something important: people may always try to hold my mother’s past against me, but I could choose to define myself. My weapon was not anger or silence. It was knowledge, patience, and the determination to prove that my story could be different.

For a long time, I carried shame I didn’t understand. But slowly, things changed. My teachers began to see my effort in class. A neighbour’s son started sharing his lunch with me.

I want to be a teacher, so no child feels unwanted the way I once did. I want to show the world that children like me can rise above stigma, that we can be seen for who we truly are, not where we come from.

As narrated by: Ali Bukar (Maiduguri, Nigeria).

This snippet is published as part of a series, The Day Boko Haram Attacked.

Discover more from Chronycles

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Published by