I

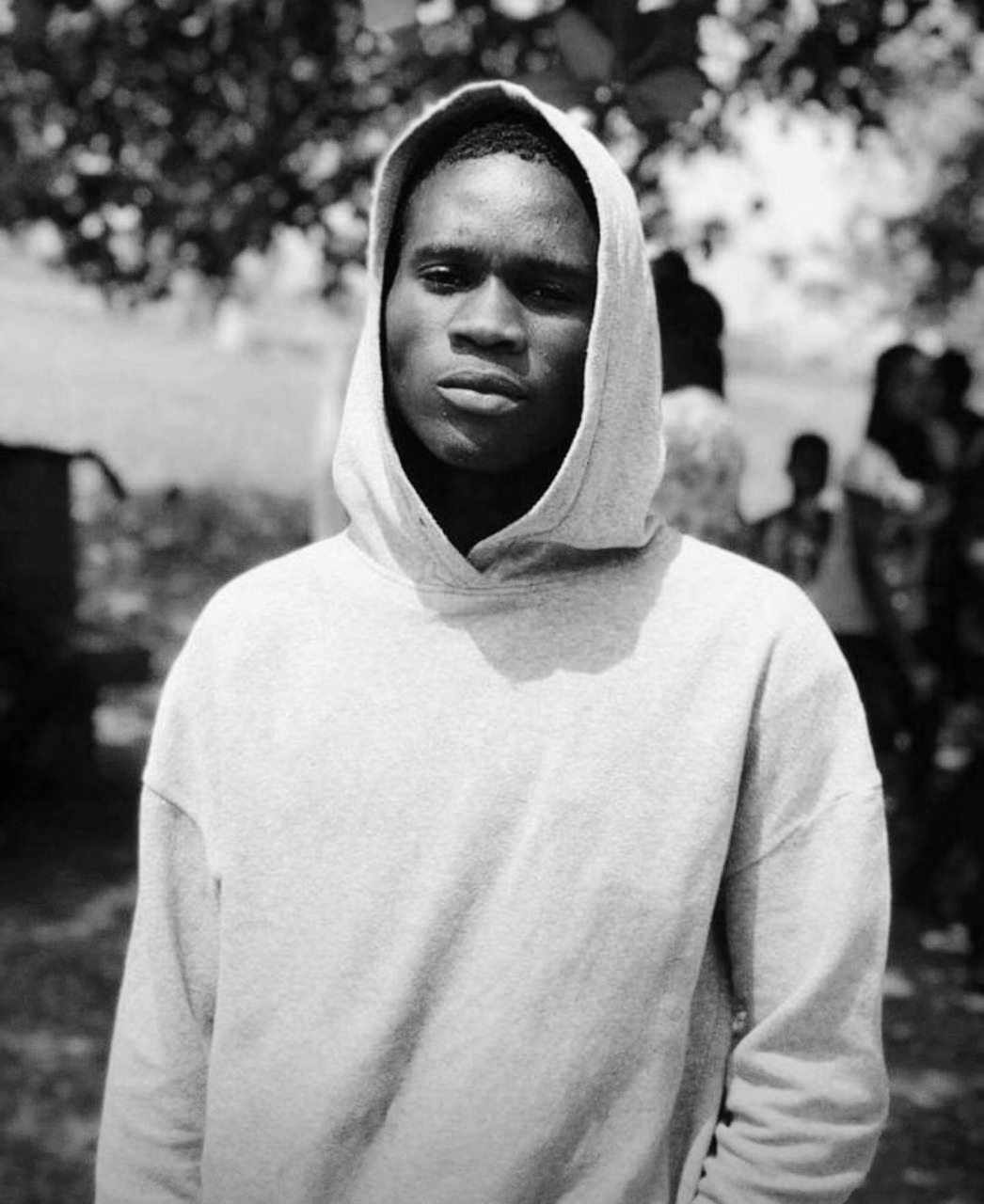

Last May wasn’t any good. It was a month I had a close shave with grief, and like cancer, it has eaten through the months that followed. The sun was just cracking out of the dawn’s clouds when it suddenly went dim on Seyyīd, my nephew. The news that sealed the bad fate came over the phone, as they often do. And the sore taste of it has refused to leave my throat. It signalled the end of my ‘first-born’ designate, the death of a personal project.

For someone who had offered condolences over the deaths of relatives and friends, this was the first time I experienced grief in its raw form, and it’s beginning to feel like I am locked in a room with it. It’s almost the end of September, and the dough left on the family table still tastes fresh … and sour.

My brother’s voice was soaked when he mumbled the news over the phone that Saturday morning. “…he has returned to his Lord,” he said, after finding the words. Some things within me broke loose. My knees couldn’t hold themselves together. Tears somehow welled up; I only blinked, and my eyes started to rain. “You have to be a man,” a random old man standing close by held me together. His words sounded like they came from a place of knowing — he must have understood what part of me had just broken, and what must have caused it.

I heard Seyyīd speak a few days before the storm hit. It was a voice I’d longed to hear coming from him. Clear. Alive. Assured. Bold and decent. Nothing gave a signal of what was to come, nothing to suggest that those were his final songs. But at the mercy of the universe, everything else, that Saturday morning, conspired to rob him of his dreams … every single one of them. If this is how it feels when a heirloom mirror breaks at sunrise, as parents and guardians, I recommend not losing sight of a child in every stage of their growth.

II

I count days on my fingers, and it is the twentieth Saturday now since the storm hit. But it started long before then. Every incident of calamity drags with it some sabab. Seyyīd strung cords of that across many necks. Mine included. On Thursday, he wrote the UTME. On Friday, he was admitted to the hospital. On Saturday, he breathed his last.

Sometimes, I feel responsible. I wear the family’s first-generation matriculation gown. As a result, the responsibility to ensure all my siblings’ children believe in education and have it naturally falls on my shoulders. He was my first nephew, so the journey started with him.

He failed the first time he attempted the matriculation examination. He failed again the second time. I became angry and scolded him in a private corner. For the first time, in my presence, he cried. He promised to change, and he set out for it. He asked that I allow him to move in with me, but because I didn’t have the means yet, I turned down his request. He listened to me and resolved to follow my guidance, nonetheless. And he remained true till the ill-fated Thursday. He had been ill, and despite it, he chose to travel over 80 kilometres to write the examination. We talked the night before and I sent some money for transportation. The ailment was already taking its toll at the time, but he stayed strong. He wanted to rewrite his name. In hindsight now, I believe he had no strength left in him. Diabetes, as they would later name the culprit, had eaten him down to the weight of a wool. All he had was love and the desire to right his wrongs and relaunch his image in the eyes of every family member. He had been a victim of his own innocence; he had indulged in adolescent exuberance. He couldn’t keep that in check, and we, the older ones, were too busy to help.

His papers were slated for 7 a.m., so he left early. Typical of the Nigerian system, I suspect the exam didn’t start until 9 a.m. and came with a lot of hassles, which would have worsened his condition. By the time he was done, all he wanted to do was find himself in the arms of his mother. Home was the only thing on his mind, but home was scores of kilometres away. He had no standby car to fetch him and did not have enough money to hire one. And he could not just resign to fate and be at the mercy of passers-by, so he mustered strength that was no longer there. And then came a trigger: an energy drink, perhaps that would lift him. He turned his head again, and Coke was in sight – a taboo for his ailment. He took it, along with some snacks. This gave him enough kick to hail a bike to cover the distance to the nearest motor park.

The bus fare was unaffordable to him. Even if he could get the driver to agree to receiving payment once they get to the destination, he was not sure his mother would be able to afford it. His mother’s petty shop is by the roadside. He could’ve told the driver, but chose not to. Instead, he stood under the sun and waved down vehicles heading in his direction at intervals. He hoped to see a kindhearted driver whose price could be slashed with bargaining. But the road suddenly became quiet, with only a few vehicles driving by in an hour. He continued to wait and hope. At this time, the spike was already happening in his system; his strength was declining fast, and his patience could not sustain his will any longer. He spent himself to the last organ in his body. For someone who finished the so-called exam by 11 a.m., he collapsed into his mother’s waiting arms twelve hours later.

Agbo (a tradomedical concoction) started pouring. No measurement, no gauge. In liquid and in solid states. He was stabilised. Until he couldn’t move any part of his body. Only breaths … in irregular, concerning rhythms. At this time, the fears had mounted. Hospital admission would mean money. So, no. He had been there a few weeks back, and his parents were still doing thrifts to settle debts incurred. Diabetes had found its seat in his body, they were told. It was the first time the word would make an appearance in the family history. They were given many instructions, including a ban on an endless list of foods, the majority of which he had had his entire life.

By midnight, everyone had exhausted the tradomedical options in their head, and his mother could not stop pacing. The entire household was now awake. So, the hospital option came alive again. They were ready. Whatever it could cost, they didn’t have it. But they were ready, anyway. It was a General Hospital with one doctor who only showed up weekly. Seyyīd was lucky; it was on one of those days that the community leaders had succeeded in prevailing on the doctor to stay through the night.

He was almost lifeless on the bed, deep into the night, when I received a scary video call. He’d warned them when he could still talk not to tell me he’d been sick. He feared I would assume he was feigning it, or that he didn’t do well in his exam, and that could make me angry, again. But at this point, at around 3 a.m., they had to betray his trust. I had an exam the following day myself, so I was studying when the call came in. In the background, it was obvious the hospital had no power supply; I could only see his body frame, almost blending into the bed. It was unsettling. We considered moving him to the Federal Medical Centre (FMC). But that wouldn’t happen until the following night, Friday, when the fears regarding cost were allayed.

FMC Abeokuta did not accept him, claiming they’d run out of bedspaces.

The state hospital became the next option. The movement happened in panic. His breathing had worsened, and his body, in his mother’s and uncle’s hands, was giving in. Seyyīd couldn’t wait for the Saturday morning clouds to disperse before he freed his soul. And that was it. That was how North suddenly turned South for the family.

III

One afternoon, I sought to know how everyone was holding their pieces together at home. I made a call, and someone married the reality of a child’s death to the convenience of a proverb. “Ọmọ kì í n lọ nílé abiyamo.” Even in death, a child never departs a true mother. I was cold. During iléyá, I didn’t go home because I didn’t know how to look into the mother’s eyes and tell her I was sorry for the loss of her son. She had entrusted him to my guidance. I didn’t know how to ask her the questions that had found room in my heart. I wanted to know why she allowed death to outwit her. I wanted to know how many pieces she was torn into when she held his lifeless body to her bosom. And when she would’ve told me all the answers, I tried to imagine how I would embrace her and tell her all would be well. I dreaded seeing her face, and so I resorted to phone calls.

This is the fourth month since the boy took the journey of finality, and every day of it, grief tastes fresh. I don’t know what to do with the feeling anymore. Each time I call home now, my instinct betrays me: “awọn Sayyid nko? Or in the middle of a conversation, I would say ‘…Mummy Seyyīd.’ This had always been my way of engaging with his mother whenever we talked about him and his siblings. ‘Áwọn Seyyīd’, ‘Mummy Seyyīd’. Two phrases that now bring torture instead of smiles. But is it not tradition to call a mother by her child’s name?

In my endurance of the sorrow this brings, the second lesson I’ve learnt — maybe as a sort of respite — is that the dead are never the target of grief; it is those left behind. Grief spares the dead of the lessons because the bereaved are its students. It sidelines the departed because they’re undeserving of its pain. Perhaps, they’re the Lord’s toast. Perhaps, they’re the innocent. And if this counts, the dead are far from the pain, maybe even at peace. We, the bereaved, are the sinners; we’re the ones made to carry the burden of their loss.

Our late loved ones are made the unwilling bearers of our sorrow. They’re the silent victims of our missteps and negligence. They’re the full measure of diyat, the token of the lesson we deserve to learn. We were to be dealt with in the ways that would be felt, and the passing of our treasure trove is worthy enough to sink the pain into our hearts and shred apart our flesh. Death takes the most adorable, the innocent, to draw those from whom penitence is actually desired closer to God’s chest. The metaphysical poem, ‘The Pulley’, just made sense to me. The grief, the pain, the hollow ache, all well-packaged as a lesson for us — it is our cross to bear, it’s the price for our torts, the whips we take for our wrongs.

Now, except I eschew the philosophy behind a dead child’s eternal stay on their mother’s back, I believe Seyyīd Adekunle Abdullahi is with us, and always will be. At home, it’s believed death is a transition, and not an erasure. With our memories woven together, he is forever alive in our stories and in our spirit.

Discover more from Chronycles

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Uhmm death is inevitable.As the Quran tells “to God we belong and to Him is our return” Nobody will be delayed for a second when his appointed time comes It’s how God wants it,ours is to take heed and pray for the dead. May almighty Allah in His mercy forgive him.

May almighty Allah forgive his shortcomings and grant him Aljanat Fridaus

It’s such a bitter and heartbreaking loss, You’re not alone, and you have my deepest condolences. May Allah (SWT) have mercy on his soul, forgive his sins, and grant him the highest place in Jannah al-Firdaws. May He also give the entire family patience and strength during this incredibly difficult time.

I was shocked when I saw it on facebook.i have to call my sister immediately, I asked her it is through she said yes and give phone to his mum.just say a little word.

Well unquestionable God.Till now,I couldn’t know how to talk to his mom again.

May Allah wipe tears on the families eye. And forgive his shortcomings.

INA LILAHI WAINA ILAIHI ROOJIUUNA.